Of all the things I’ve discovered in the last decade, Young Adult lit has probably had the biggest impact on my life. With each new book I read, my love for the genre grows, in spite of the many disappointments I’ve found along the way.

But the genre is far from perfect and, through the years, it has harbored trends, stereotypes and ideas that are extremely problematic, damaging and even dangerous.

In my opinion, the rampant girl-on-girl hate that some YA novels promote through slut shaming, stereotyping and the glorification of one girl at the expense of all the others is the real problem hurting the development and the credibility of the genre as a whole.

Not like all the other girls

One thing most YA protagonists have in common is that they’re written to be the “special” ones, usually not only because of who they are and what they do, but at the expense of every other girl in the story. They’re constantly told by other characters about how amazing and unique they are – because, of course, if a girl were to know and be fully confident that she’s special and amazing, she would be an unlovable, raging bitch – but it’s usually due to how much better she is than every other female around.

One thing most YA protagonists have in common is that they’re written to be the “special” ones, usually not only because of who they are and what they do, but at the expense of every other girl in the story. They’re constantly told by other characters about how amazing and unique they are – because, of course, if a girl were to know and be fully confident that she’s special and amazing, she would be an unlovable, raging bitch – but it’s usually due to how much better she is than every other female around.

After the success of Twilight, most of the following bestsellers featured bland and generic main characters that were widely revered as better than others, and many authors forced this characterization by demeaning or demonizing the different personalities or interests of the other girls around that main character.

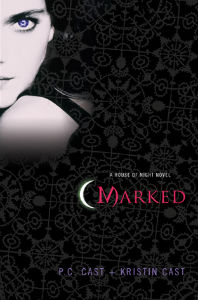

Characters like Zoey from House of Night, Nora from Hush, Hush, Luce from Fallen, and America from The Selection were constantly characterized for the reader as special and unique – sometimes not even because of what they did, but because of what others did. These MCs didn’t buy and wear revealing clothes or make-up, they didn’t chase or talk relentlessly about boys on their shiny pink cellphones, and they, specially, didn’t have sex with just anyone. They were the quiet girls that wore hoodies and loose jeans, that revile make-up or the color pink, and that did special, unique things like read Jane Austen or comic books, make art or watch Doctor Who, because that’s what made them the superior beings. All those other activities, everyone knows, are reserved for mean girls.

Mean girls

Every special snowflake in YA needs to experience some sort of generic social ordeal to sanctify her in the eyes of the reader. Bullying is not a matter to be dismissed and that some of it comes at the hands of people in the upper rungs of the social ladder is not entirely Hollywood fiction. There really are mean girls and boys that zero in on others and try to make their lives miserable.

But roughly after the release of the movie Mean Girls, almost every YA novel featured a vicious, rich, perfect, gorgeous, vain and “slutty” mean girl who makes it her life mission to bully, mistreat and brutalize the main character in between applications of lipstick and abusing the word “like.”

The House of Night series began its pointlessly long-winded saga with the introduction of Aphrodite as the ultimate mean girl. Vain, rich, spoiled, gorgeous and entitled, she was the fixed antagonist until she was brought down and humiliated – only to be replaced with an even more beautiful, ambitious and very sexual female antagonist.

The House of Night series began its pointlessly long-winded saga with the introduction of Aphrodite as the ultimate mean girl. Vain, rich, spoiled, gorgeous and entitled, she was the fixed antagonist until she was brought down and humiliated – only to be replaced with an even more beautiful, ambitious and very sexual female antagonist.

The Selection, in a similar fashion, immediately single out some girls to be the bane’s of America’s existence, for no discernible reason other than because America was just oh-so-special and they were just jealous.

Not all girls are meant to be friends and like each other; that’s an unavoidable aspect of being a teenager. But YA lit has pushed this to such a limit that it’s become a generalized experience that’s made it okay to pointlessly hate or stereotype certain characters and people. Even worse, most of these mean girls rarely get any significant characterization outside of how vile they are. They’re rarely more than gorgeous, evil beings that have nothing but hate and jealousy to impart.

In even worse cases, they are evil, hateful beings that are to be despised and reviled simply because of how sexually active they are.

Slut-shaming

Attempts at condemning and censoring women’s sexuality aren’t exactly breaking news. It’s a despicable practice that’s present almost everywhere in our media and culture, but it’s particularly startling to see it so readily embraced by so many YA authors, most of them women writing for other young women who are developing their own ideas about their budding sexuality.

The glorification of the virginal character is an ancient archetype and almost unavoidable in literature. But in YA, this worshiping cult to a girl’s virginity – which is problematic all by itself – almost always comes with the demonization of every girl who’s explored her own sexuality in some way.

[blocktext align=”right”]It’s particularly startling to see it so readily embraced by so many YA authors, most of them women writing for other young women who are developing their own ideas about their budding sexuality.[/blocktext]Moreover, even YA protagonists who have engaged themselves in sexual acts – or wish to – still have the power to demean, devalue and dismiss any other girl who’s sexually active, basing their discriminations solely on the number of sexual partners or the reason, usually the most targeted being that the girl actually likes sex and not because it was “true love.” Even worse, most of these girls are portrayed as villains that the protagonist has to defeat in some way, and their sexuality is sometimes the only “evil” characterization they get.

We have books like The Sound by Sarah Alderson, in which even new slut-shaming words like “skanktron” were made up to differentiate between all the evil “sluts” in the novel whose only crime was wearing revealing bikinis – just like the protagonist. There are others like Touch of Frost by Jennifer Estep, where a girl the main character has never even interacted with gets repeatedly called “raging slut” while the love interest is swooned at for his reputation as the guy who signs the mattresses of all the girls he sleeps with. There’s Killer Instinct by S.E. Green, where the protagonist constantly calls her own sister a whore whose only talent is giving blowjobs. And there are books like The Loners by Lex Thomas, a dystopian novel where a school divides itself into factions and the only two all-girl groups are the gorgeous, subservient, vicious cheerleaders who provide the jocks with sexual favors (and if they don’t want to, they are forced) in exchange for food, and “The Sluts,” the ugly girls named so because a few of them were raped when the school was placed in quarantine and that was their way of “dealing with it.”

To add insult to injury, the little characterization some authors bother to give the girls they’ve demeaned and demonized so mercilessly usually implies that they are such “raging sluts” because they have low self-esteem, because they’re desperate, because they want attention or simply because they know no other way of keeping a man.

Most of these novels even make a point out of having a scene in which these girls are shown throwing themselves at the feet of guys only to be tossed aside, brutally rejected and humiliated for the benefit of the protagonist, who gets shown just how much the love interest is committed to loving her and her specialness because she’s not like the rest of these “sluts.”

—

The Cahill Witch Chronicles offers a YA series featuring female characters who, despite disliking one another, admit there’s probably a better way than tearing one another down.

The worst thing about this situation is that none of these are isolated cases. In this genre, one would be hard-pressed to find a book that doesn’t feature at least one of these disgusting girl-on-girl hate trends and tropes.

They exist, of course. The recently published novel The Truth About Alice deals specifically with bullying, slut-shaming, and the world we live in where a girl makes herself better through the brutal devaluing of another with vicious attacks at her sexuality. The DUFF, another YA novel with an upcoming film adaptation, deals with the same issue, though in a very flawed way, and tries to shed light on the ugliness of slut-shaming and how that’s used as a tool to hold women back. And then there are excellent novels like The Cahill Witch Chronicles and Libba Bray’s Beauty Queens in which even girls who pretty much hate each other still understand that ripping into one another accomplishes nothing and that demeaning another girl hurts them all.

This is not about forcing all girls in novels to become lifelong companions. It’s a fact of life that nobody’s ever going to be liked by everyone. This is about giving each woman the respect they deserve. To not demonize her because she doesn’t get along with the perfect main character, to not glorify one over the other simply because they have different interests, and especially to not hinge the entire worth of a human being on their sexuality.

YA lit is a broad genre that encompasses almost every developing phase in a girl’s life, and it’s an ugly thing to send these young women the message that they can be better than others if they don’t like specific things, that they can stand taller if they walk over other women and that they will be irrevocably ruined if they even dare to think of themselves as sexual beings. This is about loving the female experience in the many different ways it comes and not stooping down to join the misogynistic practice of deciding which women are worth something and which aren’t by pitting them against each other and weighing just a few facets of their lives as if those were the only things of value in them.

For the sake of every single girl that picks up one of these books, this is a problem that needs to be eradicated from the genre so we can finally begin to grow.

—

Lorraine Acevedo Franqui writes for Girl in Capes from Puerto Rico and holds degrees in English Literature and Psychology. Her main interests are young adult lit, anything related to The Legend of Zelda and Kingdom Hearts, assorted shounen mangas and cats.

Lorraine says more on tearing women down in her series on A Strong Independent Woman (which is so big, it needs a Part II and a Part III), where she talks about female characters in TV & film.