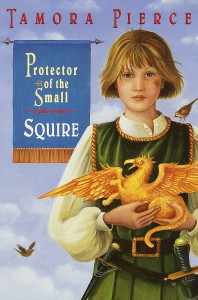

[dropcaps]I[/dropcaps] can remember very clearly the bright green spine that caught my attention, and the cover illustration of a teenage girl holding a tiny, bright orange griffin. I was eleven that year, and in the sixth grade, my love of fantasy novels was largely fueled by a little series you may have heard of about a boy wizard, but a magical creature was a magical creature, and the cover told me right away that this would be a book about magic.

A childhood-defining novel.

As it turns out, Squire is the third book in the Protector of the Small quartet, so I had to back-track and pick up a different book instead. But the path to knighthood by probationary (female) page Keladry of Mindelan marked my first real entryway into the world of fantasy — and my own path to adulthood.

But wait. I’m sure you’re thinking it. Why would a medieval fantasy novel impact my very non-medieval real life?

Recently, the Los Angeles Times published an article in which a number of science fiction and fantasy authors, including Lev Grossman (The Magician) and Nnendi Okorafor (Who Fears Death), discuss the real-life influences of their speculative work. As Grossman points out, it’s no different than writing other types of fiction: “Mrs. Dalloway is no more real than Harry Potter.”

And the true is opposite in reverse. For any given reader, Kel is just as real as, for example, Holden Caulfield, or even as real as Laura Ingalls Wilder. At eleven, living on a prairie seemed about as realistic as walking around with a baby griffin, and the ten-year-old girl who would become the Protector of the Small seemed just as real as any other girl I knew at the time.

I’ve talked about Pierce’s books in the past, and it’s difficult to write about girls and fantasy novels without mentioning her work. In my own experience, Pierce’s novels — just about all of which involving girls who use magic, though the Protector of the Small quartet is actually an exception — are the sort of books with heroines who are so real, the reader can’t help connecting.

In the case of Protector of the Small, despite the larger world full of magical creatures and the plot arc involving a magical Chamber of Ordeal, the main body of the first three books out of four involves the struggle of a girl who reaches adulthood in a climate of bullying. Her dorm is trashed and graffitied with slurs; she is outright accused of causing a number of magical incidents despite her lack of magical ability; she is the only page in history to have gone through a probationary period, and she is repeatedly told her worth is inherently less than the boys around her because of her gender.

Kel’s experiences are a reflection not only of the harassment and bullying experienced daily by both girls and boys as they go through school, but also a reflection of how some women must prepare for their adult lives. Last week, gaming journalist and critic Anita Sarkeesian’s most recent installment of Tropes vs. Women in Video Games created a misogynistic backlash so severe, she had to contact the police and leave her home due to the threats against her and her parents. Earlier this year, Pacific Standard published a piece by Amanda Hess describing her own experience with threats against her on the internet. (Warning: Both articles contain or link to the threats themselves, which are graphic and not suitable for the young.)

Libelous internet speech, threats, and harassment are daily realities for many women — and the girls who read books like Protector of the Small may very well grow into women like Sarkeesian and Hess. And characters like Kel, who stoically scrubs away the graffiti and learns to pick her battles with her critics, show girls what they may need to do in their own futures — and how they could possibly handle something so scary.

Fantasy is a way to show adventures that could never really happen, but the people living in the story are still accurate representations of humans and their experiences. Through the safety of fantasy, a reader can experience unlimited circumstances she or he may not be able to experience — or just not yet experienced — and see how it is possible or not reasonable to react to such circumstances. It’s through stories we learn what we can’t experience — and fantasy only expands on what there is for us to learn.

—

Feliza Casano is trying to live the example set by Keladry of Mindelan. She is the editor in chief at Girls in Capes and writes for all sections of the site, and she’s the one behind GiC’s Facebook and Twitter. Follow her on Twitter @FelizaCasano.