Author’s note: This article contains spoilers for the Monogatari anime series.

Anime—it can be so problematic, and yet, I love it so much! Like all forms of media, anime can be entertaining and thought-provoking, but also highly offensive. It contains its fair share of recurring stereotypical character tropes and plots, “fan service” for the male gaze, a lack of gender diversity in the industry, and an especially low number of women anime directors.

Conversely, anime often presents well-written and beautifully designed characters, highly imaginative stories not found in many other forms of media, and interesting references to Japanese history and culture. Anime also requires a high degree of artistry and talent in the production of its animation, music, and voice acting that I think many fans admire and appreciate.

In October, we discuss our Problematic Favorites here at Girls in Capes, and I have many favorite anime that would most likely qualify as problematic favorites if I were to really analyze them. Like Haruko Haruhara says in FLCL, “Eating ramen that tastes really bad can be kind of fun too.” Watching anime that’s bad or problematic can be kind of fun too!

Since it’s October—my favorite month of the year—and Halloween is coming, I’d like to talk about my love and hate for the occult-detective story Monogatari series.

I first started watching the Monogatari series back in 2009 with the first 12-episode season called Bakemonogatari, and I’ve watched the subsequent seasons as they were released. The story is based on the light novel series written by Nisio Isin.

Since the initial release of Bakemonogatari—whose title is a portmanteau or blend of “bakemono” or “apparition” and “monogatari” or “story”—there have been five seasons, each released with slightly different names.

All of the seasons have the word “monogatari” or “story” in the title, including Nisemonogatari (“Imposter Story”), Nekomonogatari (Kuro) (“Black Cat Story”), Monogatari Series Second Season, Hanamonogatari (“Flower Story”), and Tsukimonogatari (“Possession Story”), as well as a film called Kizumonogatari (“Defective Article Story”) that has not yet aired, but is set to be released in 2016.

With the release of Owarimonogatari (“End Story”), which started on October 3 on Crunchyroll, my partner and I have been rewatching the original six seasons in sequential order.

The series centers on Koyomi Araragi, a third-year high school student who, during spring break, encounters a vampire named Shinobu Oshino and essentially becomes part vampire. He befriends Meme Oshino, an oddity specialist and expert in all things occult-related, who helps him throughout the series whenever he encounters a new oddity (怪異) or apparition. This occurs quite frequently and always in connection with a new female character who quickly becomes his friend or girlfriend or sometimes is one of his two younger sisters.

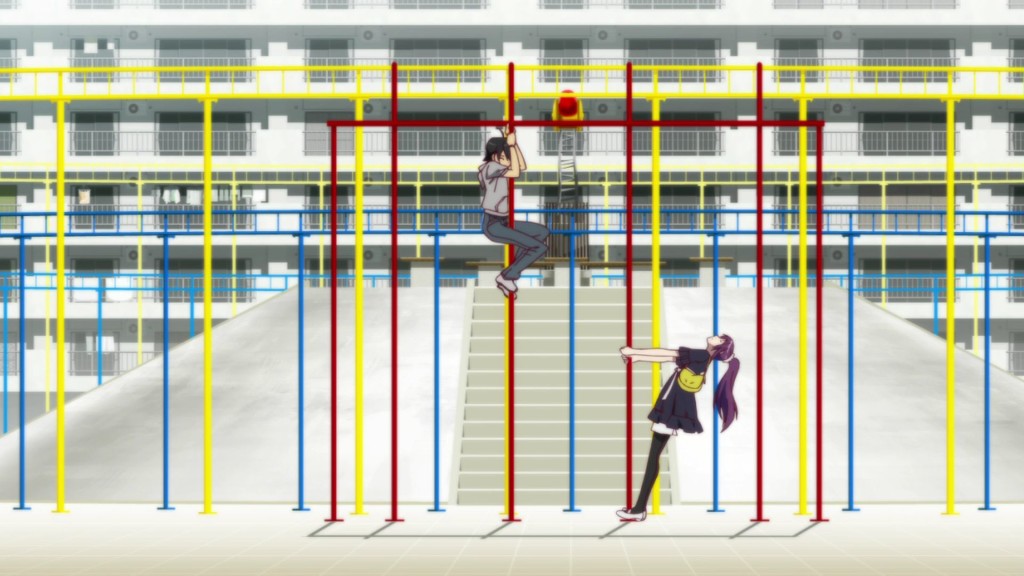

My favorite thing about the Monogatari series is definitely the animation. The style is very minimalist, with realistic backgrounds and bright contrasting colors that make it clear that one should be focusing on the characters and their conversations rather than anything else going on around them. Most anime that take place in cities show the people in the background going about their daily lives. Monogatari series, on the other hand, never shows anyone else except the characters who are important to the particular scene that is being shown. When Araragi-kun and Mayoi Hachikuji meet for the first time in episode three of Bakemonogatari, for instance, they are shown interacting in an empty playground, and when many of the characters go for a walk and talk, they are often shown in industrial or abandoned parts of the city.

[blocktext align=”left”]The style is very minimalist, with realistic backgrounds and bright contrasting colors that make it clear that one should be focusing on the characters and their conversations rather than anything else going on around them.[/blocktext]There are also these interesting blank colored screens that pop up between scenes that usually have some text on them that states something about that scene, may it be a flashback, a “black” or “red” scene, which seem to correspond with moments of violence or intense emotion, or sometimes the blank screen contains a couple of lines of text that may be Araragi’s internal monologue.

I also really like the background music composed by Satoru Kōsaki and Kei Haneoka. Each song sets the tone for each particular scene or character whose story is currently being emphasized, and it reminds me a little bit of the feelings invoked by the music in Samurai Champloo. I can almost imagine casually walking down the street and chatting with my friends with songs like “Sanpo,” which means “stroll.” The opening and closing themes also change multiple times throughout each season and are based on the current story arc.

In the end, however, what I like most about the Monogatari series is the dialogue. The entire anime consists solely of dialogue between Araragi-kun and usually one or two other characters. There are very few action scenes, so if lots of dialogue is not necessarily something you enjoy, this may not be the anime for you.

The dialogue is fairly fast-paced, and it can be difficult to follow at times, especially with subtitles. It could be described as casual, but also deep, pithy, but also verbose, and always full of banter. It reminds me a little of the quick dialogue in Gilmore Girls, although the content is fairly different.

Usually the discussion centers around life issues—from relationships between people to the stress of growing up to sexual assault—but there is often an occult aspect to the discussion as well, given that Araragi-kun is part vampire himself, but also because he has a very caring nature. He always tries to help everyone he meets who has encountered some kind of problem in life, may it be in school issues or from an encounter with an abomination.

So, what’s so problematic about the Monogatari series? I think the first problem I have with it is that it is essentially a hāremumono (ハーレムもの) or harem anime. Araragi-kun is one of the only male characters. This isn’t wrong in and of itself. It half passes the Bechdel-Wallace test. There are at least nine main female characters; however, they rarely interact with one another, and if they do, it is almost always in order to talk about Araragi.

Similar to most harem anime, almost all of the girls and women who are introduced throughout the series and who befriend Araragi in some form or another—may it be through friendship, romance, or sisterly love—are all very taken with and highly reliant on Araragi-kun for their salvation from whatever problems they’ve encountered. Araragi is always saving someone, and the stories of the women involved are never separate from Araragi’s story.

This brings me to my second problem with the Monogatari series: fan service.

If you’re unfamiliar with the term, fan service is when a creator has included a specific character, storyline, object, or camera angle in order to please the audience and give them what they want to see. More often than not, it refers to the inclusion of extra, unnecessary sexualization of characters, usually female characters, for the audience’s pleasure.

In most anime, it’s obvious when fan service is included in a show to simply titillate cisgender male viewers, like in anime like Divergence Eve or Ikki Tousen. In some anime, however, fan service can play a role in the plot or be an aspect of a character’s personality, like in the infamous School Days anime or in anime like Free!

I’m divided on how I feel about the fan service in the Monogatari series, but more often than not, it makes me wonder, “Did they have to include the naked scene or that flash of bouncing breasts? Was it necessary to the plot? Was the female character being shown in her own terms, or was she being purposefully sexualized for the male gaze?”

[blocktext align=”right”]Did they have to include the naked scene or that flash of bouncing breasts? Was it necessary to the plot? Was the female character being shown in her own terms, or was she being purposefully sexualized for the male gaze?[/blocktext]In episode two of Bakemonogatari, for example, Hitagi Senjōgahara, Araragi’s eventual girlfriend, gets out of the shower in her apartment and walks across the room naked in front of Araragi in order to get her clothing out of a dresser. I’d like to say that Senjōgahara is purposefully trying to make Araragi uncomfortable in this scene, that she is testing him, and that they are two teenagers who are still learning about their own sexuality. Yet, at the same time, scenes like this do seem unnecessary, especially as more and more female characters are introduced who continue to seemingly throw themselves at Araragi even when he has a girlfriend. Suruga Kanbaru, for example, who is a self-proclaimed lesbian, frequently teases Araragi about sex in their exchanges and about being his mistress someday.

Also, the sexual exchanges between Araragi and Mayoi Hachikuji, the wandering spirit of a fifth-grader, as well as between Araragi and his sisters Karen and Tsukihi, are especially difficult for me to accept. I can’t really understand why a character like Araragi would want to fondle a child like Hachikuji or make passes at his sisters. Is it a necessary part of the story? Is it simply harmless teasing between children? Or is there something more going on here? Are the creators catering to a mostly male audience?

I think at the end of the day, I’m still trying to wrap my mind around this unique and captivating anime and that there are more good points for me than problematic aspects. The show is without equal in regards to its animation, music, dialogue, and overall aim that I can often overlook the fan service. It would be interesting, however, if some of the other characters interacted more often. Araragi is the main character, so I understand that he is usually at the center of every episode. But it would be interesting to see more dialogue between the women of the story.

Anyway, if you’re looking for something unique to watch that will make you think, both about the subjects of the dialogue, as well as what troupes may or may not be overdone in this anime, the long and complex Monogatari series is well worth the watch. The entire Monogatari series—minus the film—is available to watch on Crunchyroll.

For a more in-depth look at fan service in the Monogatari series, check out Bobduh’s article on “Nisemonogatari and the Nature of Fanservice.” It helped me to think about fan service in this particular anime in a slightly different light.

—

Rine Karr is an Anime Writer at Girls in Capes. She’s a writer and aspiring novelist by moonlight and a copyeditor by daylight. Rine loves good food, travel, and lots of fiction, especially novels, anime, manga, video games, and films. She’s also the Chief Copyeditor and an occasional contributor at Women Write About Comics.

Looking for more on women in anime? We’ve talked about the female wizards of Fairy Tail and spotlighted some of the women in Naruto.

We’re also special fans of super-lady-centric series – check out Rine’s list of crossdressing female character anime you should check out. You can also find a guest review of CITRUS, Vol. 3 on the site. We also recommend these magical girl anime, which are currently streaming (legally!!!) online.