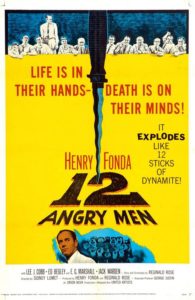

When I first saw this movie, I was in high school. We were discussing the criminal justice system and how fallible eyewitness reports could be. Nobody in the class, myself included, was particularly thrilled to be watching a black and white movie. But it stuck with me, for more reasons than one.

The movie, directed by Sidney Lumet, takes place in mostly one room. We start off in the courtroom as the jury gives their last look at the defendant, a young and presumably non-white man. I say presumably because his race or ethnicity is never stated, but the jury often refer to his “kind.” The room they deliberate in is hot and small, and everyone is ready to call what they understand to be an open and shut case. Juror 1, the foreman, decides to take a vote to see where they all stand. Everyone votes guilty, except for Juror 8.

All the evidence seems to point towards the young man’s guilt, including eye witness reports. How could this wise guy say he was innocent? Juror 8 makes the point that he doesn’t know if he’s innocent, but he didn’t believe there was enough evidence to justify sending the boy to the chair. From there, we watch as Juror 8 dissects each piece of evidence, casting doubt. Eventually the other jurors start to sway to vote ‘not guilty.’ What follows is a discussion on poverty, race, immigration and how the criminal justice system affects disenfranchised people. In 1957, I might add.

One juror asks why the accused’s lawyer wasn’t making any of the points Juror 8 was making if it was so relevant. The response was that he didn’t believe the lawyer assigned to the defendant was confident in a win, so didn’t put in any effort. The lawyer may have believed it to be as open-shut as anyone else, and had the same prejudices as the rest of the court system.

Prejudice is another recurring theme in the movie. One of the jurors was raised in poverty, so when one of the more bigoted jurors starts making accusations that the slums only produce bad people, a fight almost breaks out. A lot of fights almost break out.

One of my favorite moments of the film was when an immigrant juror corrected another juror for saying “He don’t even speak good English” instead of “He doesn’t even speak good English.” Later on, that same immigrant juror, Juror 11, calls out yet another juror for changing his vote from guilty to not guilty just because he wanted to get out and catch a ball game. Juror 11 also voted not guilty but wasn’t okay with the carelessness of how this other man was using his vote. I was a big fan of Juror 11.

The most poignant moment to me was when the most racist juror, Juror 5, started going on a long rant. He’d been saying prejudice garbage the entire movie but when he really started to get going, one by one the men stand up and turn away. Juror 5 becomes more desperate with his “that’s just they way they are, it’s in their blood” pleas. Every man turns away from him, ignoring him. He gets louder but no one is listening. Eventually he walks away and puts himself in a corner in shame. After he removes himself, the other men come back to the table to continue the discussion. What a beautiful piece of blocking. In 1957.

The only people in this movie were white men. A frustrating if accurate depiction of who gets to run the justice system, even today. If given the chance, I’d love to remake this movie with a cast of all women, from varied backgrounds. 12 Angry Women. Same dialogue but delivered by a more diverse cast. Just to see how it holds up. The Civil Rights movement was in full swing in 1957, as was the Hays Code, which usually promoted more conservative values in mainstream Hollywood. And yet this movie was able to get made while taking a very clear stance.

While the camera work was sometimes bumpy, nobody can argue the importance of the editing. 12 Angry Men has served as an example to many an Intro to Film class on how to use editing to convey emotional tension. In moments of relative peace, the camera moves freely in long shots from person to person. As discussions become more intense, there are more, quicker cuts as well as close up shots on faces. It’s not easy to make a movie about a bunch of guys talking very engaging, but the dialogue, cinematography and editing fit together exactly as they need to.

While this movie does squat for representation, it does address serious issues of prejudice in the criminal justice system. It serves as a good example too. It only takes one of us with a voice of power to change the minds of our peers. So if you’re a privileged person in a room full of other privileged people, be Juror 8.

After the movie finished in class, my teacher asked a question. Did anyone remember the color of the school’s secretary’s shirt when she came in to hand him a piece of paper? No one remembered what she was wearing. That was the moment I started to understand how easily an eyewitness report could be flawed when we’re all focusing on our own lives for the most part.

It was a very formative moment for me because I didn’t even notice her come in.