The first time I read Kindred was for one of the earliest meetups of the Girls in Capes Book Club back in 2014. It was our August title that year, and it was hot inside Main Point Books as our group of regulars settled in to talk about the book.

Kindred was not what I had expected. While I’ve always loved science fiction, I recognized for much of my early reading life that I found the Clarkes and Herberts and Heinleins of the world much too dry, and I expected to go into Kindred like a work of intellectual labor.

That was the point at which I discovered that Butler was in no way a Clarke, Herbert, or Heinlein.

Octavia Butler’s literary masterpiece could read almost as a piece of historical fiction, and in many ways, that’s what it is. While many science fiction writers focus on speculating on what might be, Butler focuses on what is and what has been, building worlds that are brutal, difficult, and so very horrifically real.

- Join Girls in Capes reading Octavia Butler’s Dawn (Xenogenesis) this month.

In Kindred, Dana is moving to a new home with her husband, Kevin, when a mysterious power suddenly yanks her into the past to save a young boy named Rufus. As it turns out, Rufus is the white son of a Maryland slave owner, and Dana’s appearance — dressed “like a man” and very, very black — is about to cause a lot of trouble.

The time travel of Kindred is mysterious and unexplained, and as she continues to go back and forth between 1979 — her present day — and the early 1800s, the reader is forced to learn more about exactly what the Antebellum South was like, and exactly what life was like for people who were slaves during that time.

One of Butler’s greatest talents, in fact, is portraying those who are victims of violence and subjugation in a manner that portrays their full humanity. In Kindred, she does this with absolute mastery, showing many aspects of life during that era and examining the question of how exactly people allowed the horrors of slavery to go on.

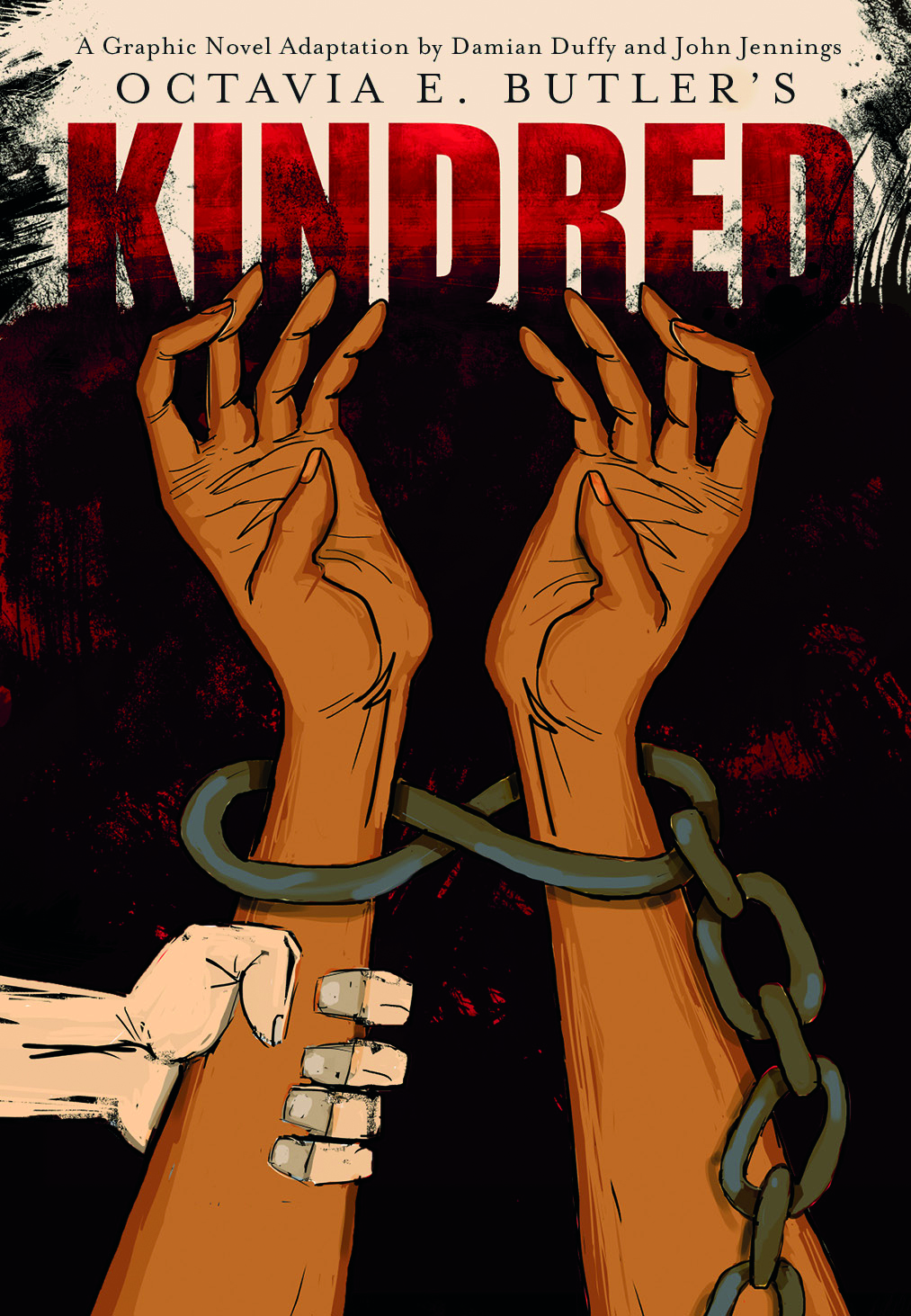

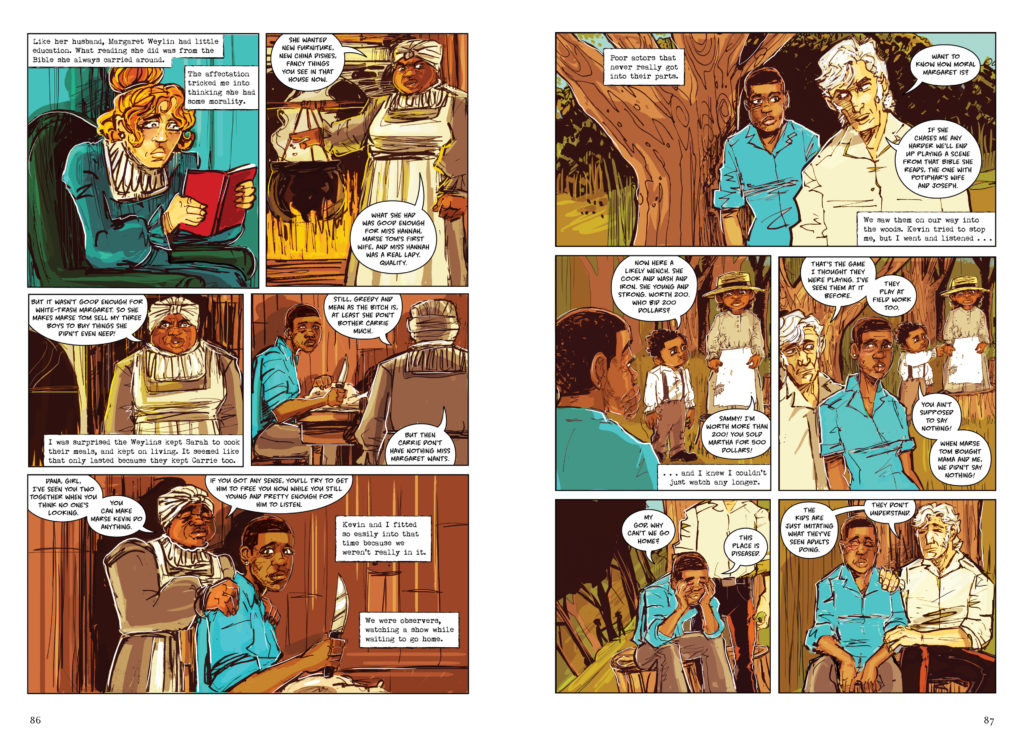

Last month, Abrams ComicArts released a graphic novel adaptation of Kindred — adapted by Damian Duffy and John Jennings — that takes the storytelling to a different level.

Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation by Octavia Butler, adapted by Damian Duffy, and illustrated by John Jennings © Abrams ComicArts, 2017

Read on for the Girls in Capes interview with Damian Duffy and John Jennings, the adapters behind Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation.

WARNING: The following Q&A and interior art samples discuss and depict a scene of graphic violence from the graphic novel adaptation.

—

Had you read Kindred prior to working on the adaptation? What did you think of the novel the first time you read it, and has that changed since completing the novel?

Kindred was the first work of Butler’s I read. It was in my sophomore year of college, and one of my creative writing professors recommended the novel. I think it was because I had written a short story for class that had some problem with the narrative voice, and she recommended I take a look at Kindred to see narrative voice done right.

I got a copy from the undergraduate library, and it had cover of the first edition, which is sort of abstract, with two women in profile overlapping an hour glass—unlike the cover of the current paperback edition, which is an African-American woman in period appropriate dress—so I really had no idea what the novel was about before reading it.

Which is actually interesting, because the novel doesn’t actually reveal that Dana’s black until like halfway through the second chapter, when Rufus drops his first racial slur. So, if you read the novel with no prior knowledge, you actually realize where and when Dana is and what that means at the exact same time in the novel the character figures out she’s travelled back in time to a plantation during slavery.

So, the very first time I read Kindred, I ended up reading it all in one sitting, simultaneously riveted and terrified in a way no other novel has made me feel.

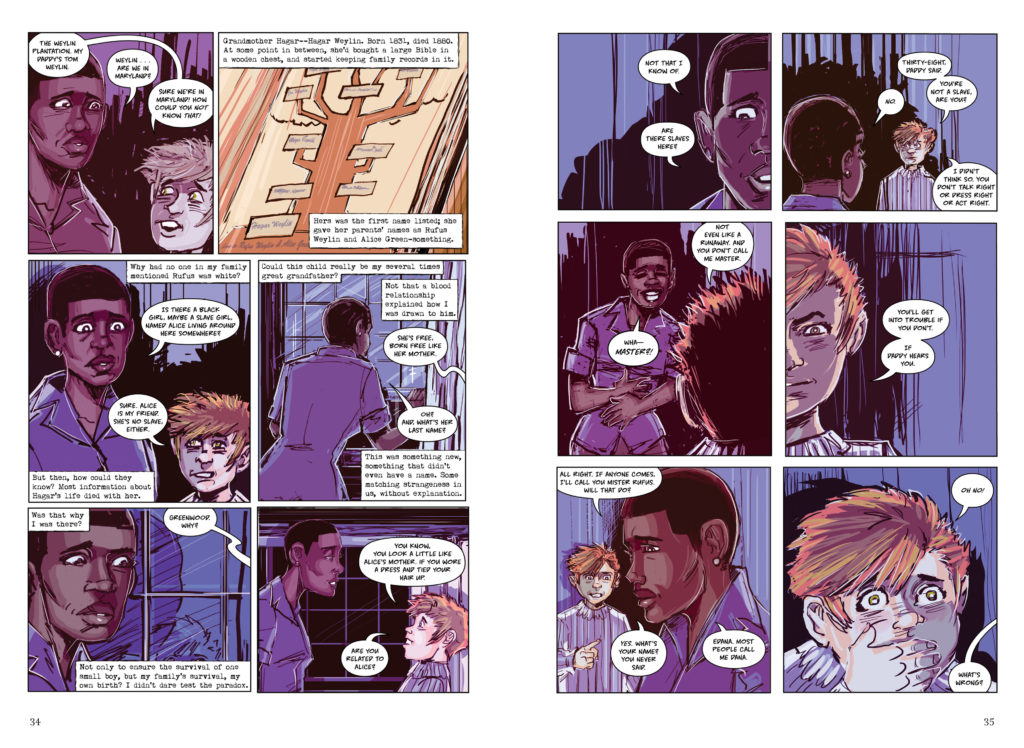

Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation by Octavia Butler, adapted by Damian Duffy, and illustrated by John Jennings © Abrams ComicArts, 2017

In your opinion, what significance does Octavia Butler and her work hold on speculative fiction as a movement?

You cannot overstate the significance of Octavia Butler to speculative fiction. For a long time, Butler was one of the only black women working in science fiction and fantasy. She was such a pioneer, and such an inspiration to so many important authors—especially writers who are women of color—that I doubt speculative fiction would be as vibrant, vital, and relevant to contemporary society without her.

Words fail to encapsulate just how foundational she is to speculative fiction that matters. Especially in the present historical moment, where we desperately need ways to imagine alternatives to the old capitalistic systems of race/gender/class-based discrimination that pose existentialist crises to humanity as a species.

Kindred is a novel that, while beautiful, can be absolutely brutal for readers. Were there any scenes that felt difficult for you to work on while adapting the graphic novel?

The violence was difficult to adapt. The first whipping scene was very difficult, although I think it was harder on John since he had to actually draw it. But Butler’s goal with the novel was to make readers feel what slavery was really like, so we approached the adaptation the same way. So, that meant we tried to retain the violence in a way that portrayed it realistically without being exploitative, which is challenging in comics, where the tendency is often to overexaggerate violence for impact. There is one small moment of magical realism that made it into the completed graphic novel that I’m proud of, but overall we tried to keep the violence very matter-of-fact, which is often more disturbing than like, over-the-top gore.

Kindred: A Graphic Novel Adaptation by Octavia Butler, adapted by Damian Duffy, and illustrated by John Jennings © Abrams ComicArts, 2017

But, I think even more than the physical violence, I had a lot of difficulty translating the emotional and psychological violence that runs throughout the novel. There’s a scene that actually takes place in Dana’s present-day, in 1976, where the character is processing some of the horrible things that have happened to her in the 1800s, that was the hardest scene for me to write and letter. Using a word balloon and a digital font to capture the kind of inarticulate scream someone would let out after an experience like that… I did and redid that page several times.

Fortunately, John’s art nailed the emotions of that scene perfectly, so that helped a lot.

Are there any works (either novels or short fiction) Butler wrote that you would cite as influential for you as a creator?

Well, Kindred, clearly, even before this project. A lot of my writing deals with family, race, and identity, and I’m sure first reading Kindred at a point in my life where I was very consciously trying to learn to be a writer contributed to that. Also, the kind of nuanced, sophisticated understanding of humanity as complicated and contradictory is something in Kindred, and in Butler’s work overall, is something that I also strive to express in my own work.

From just the standpoint of craft, I’ve also been really influenced by Butler’s idea of the “positive obsession,” of the creative work you do because you have to. That’s something I think you really need if you’re trying to make a living as a comics creator.

—

[heading style=”subheader”]About the Creators[/heading]

Damian Duffy, cartoonist, writer, and comics letterer, is a PhD student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Graduate School of Library and Information Science, and a founder of Eye Trauma Studios (eyetrauma.net). His first published graphic novel, The Hole: Consumer Culture, created with artist John Jennings, was released by Front 40 Press in 2008. Along with Jennings, Duffy has curated several comics art shows, including Other Heroes: African American Comic Book Creators, Characters and Archetypes and Out of Sequence: Underrepresented Voices in American Comics, and published the art book Black Comix: African American Independent Comics Art and Culture. He has also published scholarly essays in comics form on curation, new media, diversity, and critical pedagogy.

John Jennings is Associate Professor of Visual Studies at the University at Buffalo and has written several works on African-American comics creators. His research is concerned with the topics of representation and authenticity, visual culture, visual literacy, social justice, and design pedagogy. He is an accomplished designer, curator, illustrator, cartoonist, and award-winning graphic novelist, who most recently organized an exhibition/program on Afrofuturism and the Black Comic Book Festival, both at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library.