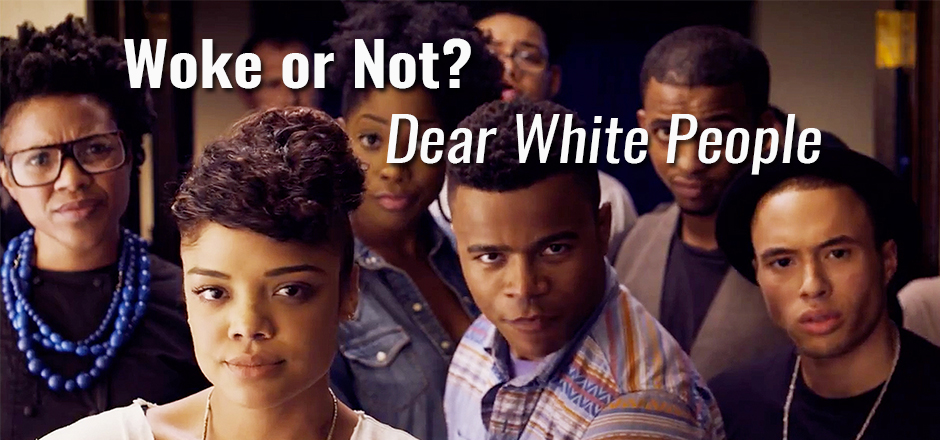

Dear White People: the series whose title alone launched countless Netflix account cancellations, endless Twitter diatribes about the mythical “white genocide” and think-pieces about how shows like these were unnecessarily divisive in our post-racial America. The release of the title and trailer, which became one of the most disliked YouTube trailers ever, singlehandedly outed hundreds of blatant racists in social media that, quite frankly, never really tried that hard to hide their prejudice and racial privilege.

After making a splash of this magnitude with its promotion alone, one could’ve expected this series to rail against the racists that opposed its release, highlight racism in its most obvious forms and call out the overtly racist America that continues to stand in the way of racial equality. What Dear White People did was quite different and a hundred shades subtler. The show is not interested in calling out outspoken racists, those who already make their own racism evident with each tweet, meme and post. Quite the contrary, the show is concerned with calling out the more insidious type of racist: the white “woke” ally.

[blocktext align=”right”]The show is concerned with calling out the more insidious type of racist: the white “woke” ally.[/blocktext]The story moves through the shifting perspectives of several black students at an Ivy League university that prides itself on its inclusiveness and diversity but whose commitment to those values is merely surface-deep. The unique identities of the students are blurred under their blackness in the eyes of fellow white students, and their complaints are disregarded as the subtler equivalent of the snowflake insult who needs a safe space.

In fact, when white people in the show get called on their behavior, the first line of defense is the First Amendment and the need for the black students to learn to take a joke. And these defenses are raised by people who, because they do not overtly discriminate on the basis of race, feel entitled to appropriate a culture they do not understand, to speak for and against issues they have never experienced, and to engage in a racial dialogue without acknowledging the privilege granted to them by their skin color.

While the show is ultimately about the black experience and how identities get lost under the prejudice of stereotypes and expectations in a white America, the show is not exactly aimed at black people. African Americans will maybe see themselves reflected in the experiences and identities displayed in the show, but perhaps they won’t find anything enlightening or groundbreaking about the series because the show presents nothing they haven’t seen, heard or lived.

The characters in the series includes a young man struggling to accept that he’s gay because of the hypermasculinization and sexualization of the image of the black man.

It presents a young woman with a strict image that refuses to veer into anything traditionally black, from her hair to her speech to her clothes, so she can be taken seriously and considered beautiful.

We see another man who must pretend to not be bothered by race comments and slightly discriminatory actions so that he can gain the approval of his white peers and figures of authority that will help him move up in politics and academics.

There are biracial characters in the show who are constantly in the defensive, anticipating questions and challenges to their blackness.

And there’s a highly intelligent young man who is perceived as ignorant by others, and who, in the most striking and significant episode in the entire series directed by Moonlight’s Barry Jenkins, has a white security guard point a gun at his face because the guard doesn’t believe that the guy belongs in that academic institution and is not there to cause trouble for the white people.

[blocktext align=”left”]This significance of these situations is addressed at the real audience of the series, the group of people that might see these scenarios as fiction and can afford to live a life without ever being positioned in any of these situations: white people.[/blocktext]This significance of these situations is addressed at the real audience of the series, the group of people that might see these scenarios as fiction and can afford to live a life without ever being positioned in any of these situations: white people. This series is for them, especially those who sat in front of their TVs, went on Netflix and hoped to nod along in empathy and understanding at the struggles of the black community, congratulating themselves on being cultured and in possession of modern sensibilities.

This series is aimed at the white guy who blasts rap songs about black oppression, loudly repeating the “niggas” in the lyrics, who then gets defensive and refuses to understand why he shouldn’t say that word.

It’s also for the white girl that reveals in a self-conscious giggly whisper that she lusts after a black guy or thinks it’s “edgy” to give her vibrator the name of a well-known black actor.

This series is for the white people who facetiously use slurs, provocative imagery and even blackface, and when confronted, tell everybody to chill and learn to take a joke.

This is for every white person who has ever brought up in an argument the dreaded “but I have black friends.”

All of these are actual scenes in the show.

Moreover, this show is also for the white person that shares a meme or post against racism but has never left the comfort of their own house, much less the security of their own white privilege, to actually start a conversation or engage in some sort of concrete action to remedy the situation. This is a series for the white person that can afford to not read news about police shooting black unarmed people because it is too “upsetting,” or who thinks that there is some merit to the Black Lives Matter vs. Blue Lives Matter or All Lives Matter debate.

Dear White People, while slightly uneven in its narrative and character development and even sometimes clumsy in its approach to hot topics, clearly aims to dispel the notion that we exist in a post-racial America, even in institutions of higher learning. The series wishes to make people understand that acknowledging that there’s a problem is only the first step, and that it needs active participation and comprehension if one wishes to eradicate the problem.

This show is angry at the fact that social consciousness has become an accessory, a cute little hobby to adopt for those whose lives are not affected by these issues as long as there’s no introspection or accountability involved. And it has no problem with expressing that anger with an in-your-face attitude and emotional rawness in between the jokes and pop culture references.

Upon finishing the first season, my first thought was that, while most of us wish to qualify as “woke,” the truth is that we’re not. We’re still dormant under the complacency brought on by the ludicrous idea that we live in a society that has moved beyond race and has not merely deluded itself into thinking that it could avoid doing so without holding itself accountable.

We are far from woke, dear white people.