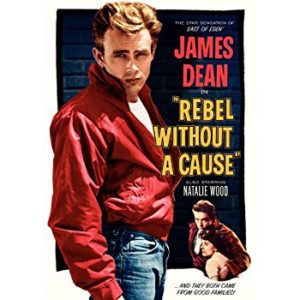

For most people, when they think of James Dean, they think of him in a white t-shirt and a blood red jacket. From Marty McFly to Fry from Futurama, his role in Rebel Without A Cause has been referenced and burned into pop culture’s subconscious. It’s almost transcended the movie itself.

Nicholas Ray’s 1955 Rebel Without A Cause (or as I like to call it, Daddy Issues: The Movie) is to me the definition of a problematic fave. I am left uncertain if the film’s examination of gender roles within a family unit is criticizing the incredibly problematic social norms of the 50s or lamenting the loss of them.

We meet Jim Stark (James Dean) in a drunk stupor. After being pulled into custody, Jim bumps into Judy (Natalie Wood) and Plato (Sal Mineo) at the police station, two more restless youths with their own family issues. We find out that Jim and his family had recently moved to this town because he kept getting in trouble at his old school. So when Jim gets in a knife fight with a group of ruffians on his first day at his new school, it sets off a chain of tragic events that ultimately bring our three misfit characters together in a makeshift family.

I’m not going to lie: this movie is my exact aesthetic. I live for that Greaser style. So I ate up the costuming and overall production design. The cinematography made the images on screen look just delectable. From the vivid use of red to the light projections dancing on the actor’s skin, it was just pretty to look at. The music seemed a touch heavy-handed at times, but I think that was typical of the era.

I found the dialogue to be very interesting, if a little unnatural. It was complex and layered, much more like a play than that of a typical Hollywood hit. It got right to the point of these character’s emotions while still concealing a certain level of understanding on the character’s part. They are teenagers, after all.

But what makes this movie problematic is the examination of gender within a family dynamic. Jim’s major issue with his father is that he lets his wife boss him around. The height of Jim’s frustration with his father is when he finds him in a laced apron, bringing dinner on a platter to his sick wife. Jim makes the comment that he thinks his father should hit his mother next time she tries to demean him.

This all makes sense given the social and gender norms of the era. But is the movie portraying Jim as a sympathetic character because he’s right about being upset? Or we supposed to feel sympathetic because Jim has become a victim to the era’s strict gender and social norms? Probably the former, but a girl can dream.

Jim’s advocating for violence against his own mother is at total odds with how he treats his own love interest, with care and even sweetness. The love interest, Judy, has her own daddy issues. She throws a fit after her father refuses to let her kiss him on the mouth. Yikes. Plato’s father has separated from his mother, who is never home. He acts out by murdering puppies. Double yikes.

It’s repeatedly stated that Plato wishes Jim were his father, putting Judy in the mother role. However, a lot of people have read Plato’s attraction towards Jim as romantic, reading Plato as queer. I personally did not see it, and I’m constantly looking for that stuff. I saw his almost creepy attachment as more of a father/son relationship. Then again, this is the same movie where Judy pitched a fit because he father thought she was too old to kiss him on the mouth. What I’m trying to say is that Freud might have a lot to say about this movie.

There is only one person of color in this movie, Plato’s maid/nanny. It isn’t an unrealistic representation of black women in the 1950s, if an uncomfortable one. Black women raised a whole generation of rich, white American kids and were still treated dismally. While these characters were all interesting in their own right, Plato’s maid may be the most sympathetic. She genuinely cares for this deeply troubled young man and at the end, is left with nothing but sorrow.

This angsty greaser classic makes for an interesting movie night. It’s one of my personal favorites, problematic as it may be by today’s standards. But that’s a benefit of historical pop culture, we get to glimpse into what was acceptable years ago.

Viewing and criticizing these films isn’t endorsing their problematic aspects. Censoring these films is a form of erasure. We cannot afford to erase the struggles of the past, or we’re bound to repeat their mistakes. So go into Rebel Without A Cause realizing it’s a product of its time and you may come out on the other side with a better understanding of that time. And why that time sort of totally sucked.

[coffee]