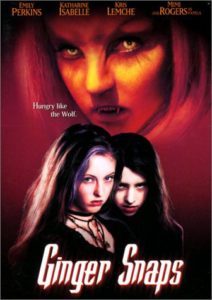

Based on what the movies have told me about what it’s like to have a sister, I grew up thinking, “thank GOD I never had one.” Even at their purest and most well-meaning, nearly every sisterly bond I’ve seen portrayed on screen includes some kind of jealous act or competitive undertone. Ginger Snaps (2001), the John Fawcett-helmed teen horror starring Emily Perkins and Katharine Isabelle, is no exception. But what makes the Fitzgerald sisters unique is that we’re catching them both at the most crucial time in an adolescent’s life, when emotions run high, relationships are tested, and young, delicate flowers bloom into hairy, raging beasts: the First Period.

It’s a subject that has gone largely unexplored in film, but lucky for us, Ginger Snaps hilariously and grotesquely encapsulates that special time through two key perspectives: Ginger’s, who is going through “the change” while simultaneously becoming a werewolf; and Brigitte’s, who has yet to get the curse and dreads its consequences. These twisted sisters provide preteen girls everywhere a new way to deal with the perils of puberty: by finally embracing the beast within.

Ginger Snaps may sound like it has a scary premise, especially for a younger crowd, but really it serves as candid,  relatable material for all those who are experiencing (or about to experience) changes in their body.

relatable material for all those who are experiencing (or about to experience) changes in their body.

Here’s a helpful synopsis for mothers and daughters to review: the Fitzgerald sisters, outspoken Ginger (Isabelle) and timid Brigitte (Perkins), are obsessed with death, hate their Ontario suburb of Bailey Downs, and delight in photographing themselves as corpses. For this blatant condemnation of small town life, the sisters are punished by teachers and mocked mercilessly by peers. One night, after botching a plan to steal the precious dog of head bully Trina Sinclair (Danielle Hampton), Ginger is greeted by the unwelcome red tide for the first time. Naturally the blood attracts a werewolf, and Ginger is attacked.

After being saved from certain death by local teen drug dealer Sam (Kris Lemche), the girls rush home to tend to Ginger’s injuries, only to discover that they’re already beginning to heal. Ginger swears Brigitte to secrecy about the attack and getting her period, but their perky mother Pamela (Mimi Rogers) finds bloody sheets in the wash and becomes overjoyed. She bakes a “Happy First Period” cake for Ginger, who accuses Brigitte of spilling the beans, which is the first rift in their relationship.

As the days go by, Brigitte notices Ginger’s behavior getting more and more erratic, and she turns to Sam to find answers. The growing distance between the sisters causes Ginger to have unprotected sex with the dreamy jock Jason McCardy (Jesse Moss), who becomes horrifyingly infected with the werewolf virus as a result.

Desperate to cure her sister of jock-screwing, dog-devouring, and tail-growing, Brigitte finds herself at Sam’s greenhouse frequently. Sam, a studied man of the herb, suggests monkshood as a cure. The pair test it out on Jason first, and find it a success.

But before they can get the cure to Ginger, she decides she simply doesn’t want to be cured: she loves the power, her allure, her speed and heightened senses. She kills her former enemies—Trina the bully, a guidance counselor, a janitor she deemed lecherous—and bursts into a Halloween party to proclaim her liberation. Sam and Brigitte are forced to lure her back to the Fitzgerald household, where she inevitably goes full wolf. After infecting Brigitte and mutilating Sam, Ginger is finally killed by her sister, who is unable to administer the cure. We leave the sisters on the floor of their shared bedroom, with Brigitte’s impending transformation looming overhead.

While it might not give the same advice as your old American Girl’s Guide to Puberty, Ginger Snaps provides its audience multiple approaches to understanding and dealing with young womanhood. Ginger’s arc serves as a heavy-handed but deliciously entertaining cautionary tale, warning teen girls to always educate themselves about their own bodies, and to reach out the moment they feel overwhelmed. Ginger withdraws from Brigitte almost immediately after being attacked, depriving herself of the one person she could trust with anything.

This only exacerbates her fear about what’s happening to her body, leading her to frantically shave off her werewolf hair and even slice off bits of her growing tail in secret. The fact that she tries to ignore her many aches and pains, rather than find a way to remedy them, is what causes her to kill the neighbor’s dog, for example, and to attack several high school boys. Essentially she tries to self-medicate instead of getting help, and that route only leads to her demise.

Not everything about Ginger’s story is negative, however. Her sexual awakening happens at an alarming and sometimes disturbing rate, but it’s not every day you get to watch a young woman fiercely, unapologetically fulfill her carnal needs. My favorite line in the movie is when Jason and Ginger are having sex in his car and he says, “Hey, take it easy, just lie back and relax,” to which she replies, “No, YOU lie back and relax.”

When it comes to her sexuality, Ginger is consistently portrayed as confident, capable and in control of the situation. Her only fault here is failing to use protection, and we see the really, really gross consequence of that when Jason demands to know why his face is full of boils and his teeth are growing out of his mouth. True, he gets cured by Sam and Brigitte’s monkshood, but the film does a fantastic job of showing the dangers of being unprepared. Get your freak on, ladies, says Ginger Snaps, but do it with condoms.

The other main female perspective in the film is Brigitte’s, who has yet to experience menstruation or even the vaguest hint of sexual desire for another human being. She represents the adolescent who has virtually zero knowledge of puberty, who might be terrified of what’s about to happen, and her journey should be taken to heart by such an audience.

At the start of the film, she despises anyone in Bailey Downs who isn’t Ginger, and agonizes over the idea that her sister might “go average” on her. She reacts to Ginger’s period with disgust, she would prefer spinal cancer to menstrual cramps, and she links sexuality to destruction—as seen when she makes guesses about Trina’s death, telling her sister that it will most likely happen in a beauty store. Brigitte serves as a model for those who feel like outcasts, who maybe actively avoid talking about sex and menstruation, and because of this she provides an entirely new way of handling it.

Unlike Ginger, who enjoys and embraces her womanly powers quite abruptly, Brigitte takes the slower, steadier route: observe, internalize, strategize. She watches Ginger with keen attention, keeping track of her cycle on an ovulation calendar, taking note of the hair in the trash, and even lifting up Ginger’s sheets to get a glimpse of her tail. She realizes the werewolf curse could very well happen to her, and that the period curse WILL happen to her, and instead of staying silent she talks to someone. True, that someone is teen drug dealer Sam, but he’s a bit of a misfit like her, and is glad to offer help.

Brigitte is never forced to suck it up and tell an adult, she’s never made to compromise her sense of self—instead she is able to monitor the situation at her own pace. After all, the monkshood cure is discovered about halfway through the film, and instead of rushing to cure Ginger, Brigitte experiments on Jason first. This character is showing girls that it’s more than okay to take time, to learn about experiences before diving into them. That’s a pretty big switch in roles from the girl who played Beverly Marsh in the 1991 IT!!

And one final note about Brigitte: she even manages to connect with her ultra-Stepford mom at the end of the film, giving girls who identify with her a positive scenario to keep in mind when dealing with their parents. Granted, Brigitte’s conversation with Pamela is mostly about burning down their house to hide the evidence of Ginger’s crimes, but for the very first time, we see Brigitte being honest and genuine with her mother, and Pamela responding in the same way. Who knew a movie about a teen werewolf could bring mothers and daughters together, huh?

Two sisters, two drastically different ways of dealing with puberty. Ginger Snaps certainly gives young women a lot to think about—the fear of losing control, the excitement of growing up—but it’s way better than nothing at all. I mean, seriously. Given the choice between a poorly animated twelve-minute educational film and a crazy, campy Canadian werewolf movie, I’d rather have the werewolf movie teach me about menstruation any day.